Thank you Failure - Oregon Timber Trail

On June 1, 2018, the Durango-Silverton Narrow Guage Train (allegedly) expelled sparks or burning ember from its coal-burning steam stack and ignited a wildfire. This fire (named the 416 Fire) quickly engulfed the San Juan National Forest 10 miles north of Durango. Eventually joining forces with the nearby Burro fire, it would go on to be one of the largest and most devastating fires in the state’s history reaching over 54,000 acres before being contained nearly two months later.

The 416 kept segments of the Colorado Trail (CT) closed for weeks.

Having spent six months planning and training to do the CT, my trip was very much in question and I had a narrow window for making a decision. I could stick to my plan, and hope for the arrival of the monsoons and a re-opening of the trail, or I could punt. Not wanting to risk bad air quality at high elevation or other safety issues, I made the conservative choice and elected The Oregon Timber Trail (OTT) as a back-up.

Weeks of indecision while watching weather reports, pouring through social media feeds, and watching the #416 twitter feed were replaced with a single-minded, forward motion. I needed to pedal my damn bike.

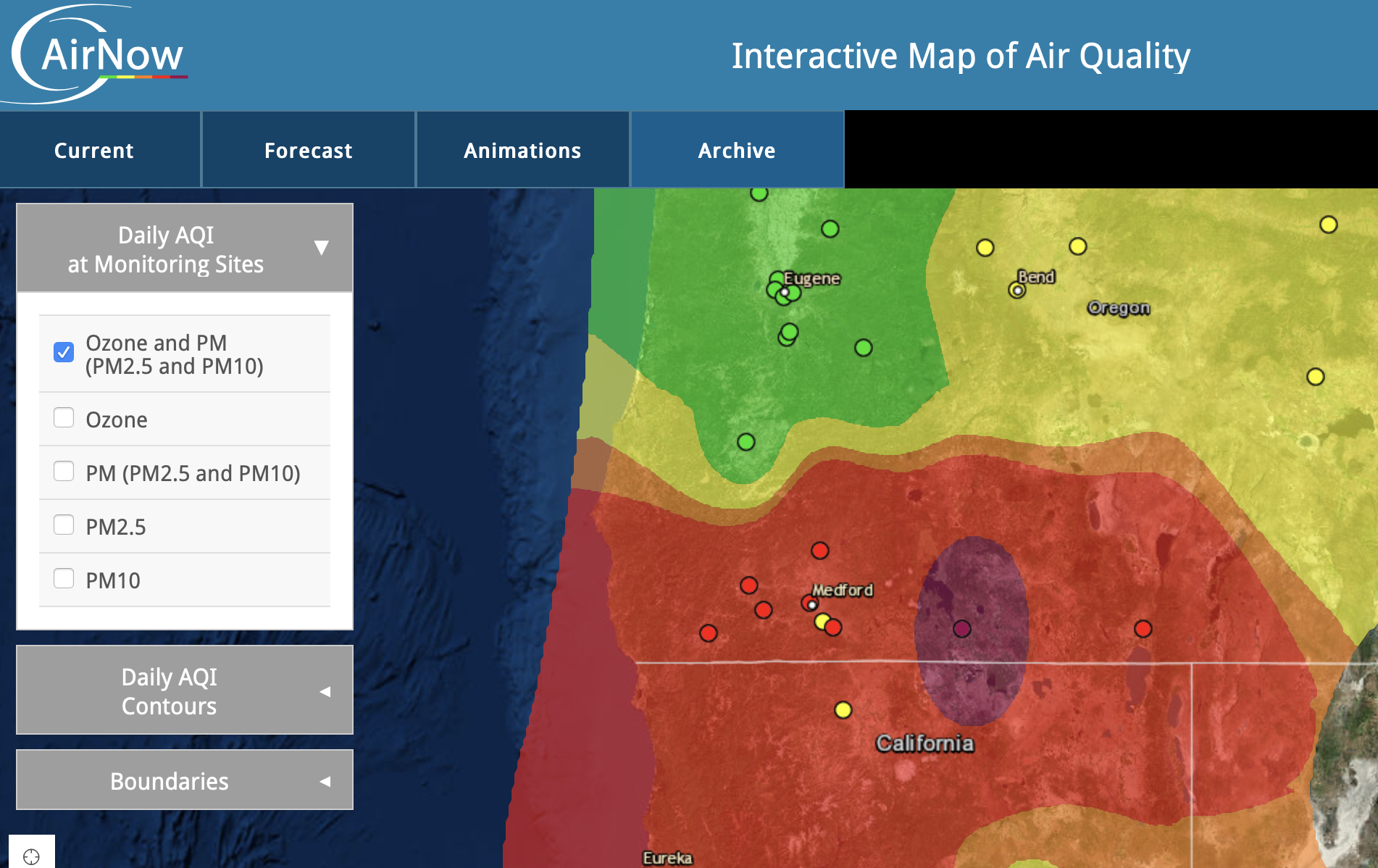

So you can imagine my dismay that day in late July as we drove south from Portland as I watched the Southern Oregon/NorCal air quality chart turn rapidly from green, to yellow, to orange (and incredibly Colorado turn to all-time perfect conditions). The universe and I were at odds this summer, but we’d come to terms eventually.

Leaving from Alturas, California, I’d decided to add the Alturas High-grade approach to my OTT attempt. It seemed only right to start at the new beginning. Sadly, this extra segment may ultimately have been my undoing.

Not because of the added distance and climbing, but because it put me about a half day closer to the approaching tide of Orange, Red and eventually Purple air quality. It was a half day that I simply couldn’t outrun.

Day 1 was hot, mid-90’s, and the skies were very hazy. But unable to smell anything too alarming, I felt confident in starting the journey and riding toward clearer skies. The initial paved section gave way to gravel after about 12 miles and my mind stayed occupied by a heady climb that put me up into some Ponderosa Pines. The going was slow and I attributed my slow pace to being up around 7k feet elevation. It wasn’t until evening that I began to realize how little I’d eaten, something very unusual for me. Anxious to stay on my schedule and knock out the High-Grade Approach on my half-day of riding, I pushed pretty hard into the evening. But when the gravel climb finally gave way to single track, I missed my turn and descended a few hundred feet of loose sandy soil before catching my error. Making my way back to the ridge had me throttled with effort. My head was pounding and a mad dash for the woods with a GI emergency left me pretty confused about my condition.

Dinner wasn’t an option. I set up my shelter, collapsed into my bag and listened to my head pound with my racing pulse. Something was definitely not right. 54 miles, 6500 feet of climbing. Even as loaded as my bike was, it shouldn’t feel like this.

A few hours of sleep and I woke determined to rally and make up the lost ground. I felt it would be better to get moving immediately since I still lacked any sort of appetite and try to reach the official starting point of the OTT. The day began with some bike whacking, but I was happy to be on single track no matter how over-grown. The skies were another matter and they forewarned of trouble yet to come.

Cresting the ridge above where I’d made camp gave me reason to be optimistic. The ridge was pronounced, and the valley I’d climbed from seemed to be holding the majority of the bad air. I hoped it might act as a levy of sorts and protect the adjacent valley so I could find some clean air and perhaps recover a bit. For a time, this was the case. I descended down to the campground at Cave Lake which marks the proper start of the OTT and decided to try some breakfast.

Choking down a little oatmeal and a coffee, I decided to show some discipline and stick to my plan of washing my one chamois at every opportunity. A bit of sunshine to dry things out and I was back on the trail. Starting the OTT mid-morning of day 2.

The trail riding on Day 2 was pretty green but great fun. Lots of down trees and a bit of route finding. I had a terrible time following the gps track at one point as it connected a couple of road grades separated by about 200 vertical and no discernible trail. Full on bike whack and just trying to follow the chevrons of my Wahoo screen. There were a couple of bike heaves up and over downed trees and tons of snags and undergrowth biting at the ankles. Ultimately I broke through and started a good healthy descent. Water was becoming pretty scarce and the amount of livestock affected streams was a bit troubling. I’m no stranger to getting upstream of the cow patties, but this was getting a bit ridiculous. Having crossed some ranch land near Highway 140 and done a monster paved climb, I had to shut it down early with the hopes of eating some dinner and making up for my sleep deficit. The 40 miles and 7400 feet didn’t really tell the tale of how difficult the day was and I put my mind to recovery. A second day of very few calories left me frustrated. Only choking down 1/3 of my Good Eats dinner and economizing water at a dry camp wasn’t helping. “BUT THE RIDING IS SO GOOD!!!” I kept telling myself. And it was! I was urging myself on, stoking the flames to push through whatever was happening to me.

Unfortunately the morning of Day 3 did little to improve my station. I was a wreck. Disorganized, clumsy, and just not thinking clearly it took me far too long to breakfast and break camp. I had a few minor mechanical things to tend to as my dynamo hub wires had been dislodged during the prior day’s bike whack. My dexterity was poor and I was just hoping that the coffee and bit of oatmeal would help me rally, which eventually it did. Always better once you're moving.

I found my OTT experience was one of extremes. I was so absorbed in the excellence of the riding, the remote solitude, and what I could only imagine to be amazing vistas that I often was able to put my physical state behind me. ENDLESS singletrack and fully sessionable bits left me giddy and wanting more. But the bonk was ever creeping. I just couldn’t eat, and water was increasingly scarce.

Final water source for many, many, many miles.

Day 3 was the absolute best riding of the trip. Some of the most unrelenting climbs I can remember would give way to incredible views. Sadly, they were all socked in from smoke for me, but the sense of it was there. I knew I had a line of sight to Shasta and 3 Sisters from the same ridge. I knew I would have to come back for clearer skies another day. What I didn’t know, was that I was heading for the biggest bonk of my life.

At about 4pm on day 3 I took stock of my situation. It had reached 96 degrees, and while I was managing it ok, the profile on my map made me shudder. I had several thousand feet of climbing remaining and from what I could tell it was going to be steep. I’d given in to the reality that I was suffering from smoke inhalation and I was becoming truly ill. I was walking up shallow grades, my heart continued to race and my energy was just non-existent. With another significant climb ahead of me I was becoming concerned about heat exhaustion.

The previous year I’d taken to carrying a 2-way sat device, the Garmin Explorer+, when I was on solo trips in the backcountry. I knew there was a motel in Paisley, OR but I hadn’t planned on making the 6 mile side trip into a town. Now, my mind wouldn’t let go of the idea of air conditioning and getting my body temperature down. I buried my pride and texted my wife.

I knew she’d been dot-watching and finding info on Paisley would be no problem. Within 30 minutes I had a response from her that she’d set me up with a room, now I just had to get there.

The next few hours were the deepest I’ve ever had to dig physically in my life. Though I’d carried a lot of capacity, I was burning through water with the temps and slow progress. Now, I’d completely run out. Around 6, walking the bike up a gentle incline, I half sat, half collapsed on a switch back and decided this was going to be a moment to gather myself and rally. A mental inventory reminded me I had a Honey Stinger buried in my saddle bag. Honey’s part water right? So my hazy logic told me. The gel hit my system and I truly feel that without it, I would have been faced with ditching the bike to walk out. I was annihilated.

Once I was moving again I quickly came to a dried stream, followed by another. At the third, I was able to find a trickle of water rolling across cow patties guarded by a swarm of mosquitoes. I went for it. Filtered and treated, I was able to get a few swigs of some of the gnarliest water I’d ever had the pleasure of enjoying. But it got me moving.

The descent, had I been fully present, would have been incredible. But at this point I was chasing daylight and the countdown to the river and pavement that would lead me to Paisley.

I would eventually arrive around 10:30 at night.

This is not Durango, Colorado having a beer to celebrate, nor is it Hood River. This is Paisley.

After another night with no dinner, I made my way to the Paisley diner for a country breakfast, not really knowing if I’d be able to put it down. Fortunately, all went well. But come check out time I was in no condition to go anywhere and the smoke had shown no sign of improving. I decided on a zero day, and tried to sleep as much as possible before making some decisions that evening.

After much rest and dinner, I gave myself some options. 1. get on with it and hope the air clears. 2. skip the next segment and get further North. 3. bail.

I decided I’d check the skies in the morning.

At 6am on day 5, I peered up the valley and saw my situation had worsened. The early morning light twisted unnaturally over the river in a brownish haze. The air was old and toxic. The decision was made, but it wasn’t without some agonizing regret and complication. My only exit required 100 miles of road riding below Winter Rim and along the shores of Summer Lake. An expansive and shallow alkali lake whose waters I would never see in the 15 miles I rode its boggy shores. Paisley gave way to Silver Lake which eventually led to La Pine. Head down, soaked bandana over my face, right ear bud playing podcasts; I settled in to the work at hand.

Summer Lake, OR

The oldest human remains in the Western Hemisphere were found in the Paisley Caves created by Summer Lake. Today, it’s a low water line but still home to endless species of birds. I had the good fortune to see a badger cross the road in front of me and warily keep its eye on me as I pedaled passed. Days prior, a bobcat had crossed me in a similar manner. These unrelated events stood out for me as a traveler in someone else’s land. I was the stranger, and they were letting me through, but they watched always.

I arrived in La Pine around 2:30 and caught a shuttle to Bend that afternoon. Even in Bend, the smoke was brutal and I took solace in that beneath the weight of my decision to abandon the trip.

Thank you Failure.

It took me a few weeks to utter those words.

Abandoning had put me in a genuine funk. Maybe it was the extreme generosity of Jeff and Ali who drove me 7 hours to the start. Maybe it was the fact I’d carved 10 days away from home when there was so much to do there. Maybe it was the selfishness of a big adventure while my wife continues to fight a disease that keeps her grounded. The time away from work, the last minute change to “Plan B”, the financial resources, the hours of planning, the training…all of it. It just seemed so god damn frivolous.

And to fail.

Not even really just fail, but stopping before I really got started, it just sucked. There’s no eloquent way to write it. That’s where my mind was at in the days following my self-extraction from the Oregon Timber Trail.

But as is often the case with me, some time and distance gave me perspective. I came to realize I needed this failure more than success. I needed to bump up against some limits and to test the quality of my decision making in difficult conditions. I needed to fail, in order to not.

2018 hasn’t gone to script. Hell I’m writing this with an ice-pack on my elevated knee while the rest of Oregon descends on Bend for the Cross Crusade. But these little adversities are nothing more than reminders of what’s important in life, and I’ll stay focused on that. The next adventure will come, and when it does I’ll lean on this year for strength and experience.